Until my friend Chitrita

gave me the book, I hadn’t heard the name of Colston Whitehead. Neither had I come

across the string of words

Underground Railroad. I will come to Colston

Whitehead shortly, but before that, let me describe what “underground railroad”

means in the context of American history.

Chattel Slaves in

America: Men, women, and children kidnapped from Africa, ferried across the

Atlantic chained to the hull in dark holds of ships, and sold at port-town

markets to white American farmers. Besides suffering the ignominy of being

treated as personal possession, they lived a life of such relentless hardship

and pain that very few would live to become old.

Young women were also

used as producers of more slaves; they were allotted to male slaves with strong

physique, unless they produced mulatto babies as consequence of rape by owners or

their overseers. Children, routinely taken away from mothers, were made to work

in fields as soon as they were able to walk. Rape of and other sexual brutality

on women were so common that we hardly see black Americans who are really

black. When Alex Haley, the author of the 1976 novel Roots, The Saga of an

American Family went to the heart of Africa in search of the hamlet from

where one of his eighteenth-century forefathers, Kunta Kinte had been

kidnapped, Haley was shocked to see the unblemished blackness of the African

skin there.

For the slightest

lapse, real or perceived, slaves were subjected to often sadistic torture by

their white

owners and their overseers. Lashing with a rope whip with nine

notches – disingenuously named cat-o’-nine-tails – was the least punishment.

The worst was reserved for people who had tried to run away and got caught. For

a man, it could be cutting off his penis, shoving it into his mouth, stitching

his lips and letting him die a slow death accompanied by even more torture, as

his white owners and their guests watched the spectacle while having dinner in

the open. For a woman runaway, it was so brutal that I find it difficult to

type out.

Given the life

they lived, many slaves fled their masters every year despite the humongous risks

involved. On the other hand, there were professional “slave catchers”: white

men who made a living out of tracking down and bringing back runaway slaves to

their masters, sometimes from thousands of miles away. It was possible to

recapture fugitive slaves even from the North American states where slavery was

illegal, thanks to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 which granted immunity to

slave catchers and compelled local officials to assist them. As the law

required scant documentation to claim that a coloured person was a fugitive,

slave catchers also kidnapped free Blacks, especially children, and sold them

into slavery. The Wikipedia (accessed on 31 August 2020) says:

The law deprived people

suspected of being slaves the right to defend themselves in court, making it

difficult to prove free status. In a de facto bribe, judges were paid a higher

fee ($10) for a decision that confirmed a suspect as an enslaved person than

for one ruling that the suspect was free ($5).

However, the world

is never devoid of people who would help their less fortunate brethren. Lots of

people unknown to each other, both white Americans and free African Americans, collaborated

to set up a network of safe houses and secret passages that were used to transport

slaves from the southern states of America. Their destination was either British

North America, most of which is presently Canada, or the northern American

states which were more tolerant towards “negroes” in varying degrees, particularly

certain cities like Philadelphia and New York, the latter being a “factory of

anti-slavery sentiment.”

The “Underground

Railroad” was neither a railroad, nor was it underground; it was a metaphorical

name given to the network narrated above. The “railroad”, which did not have

offices or official documents, began in the late 1700s and grew steadily until

the American Civil War (1861-65). “One estimate suggests that by 1850, 100,000

enslaved people had escaped via the "Railroad".” [Wikipedia, accessed

on 31 August 2020]

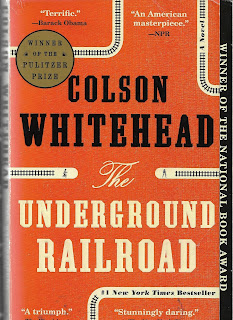

What if such a

subterranean railroad actually existed in the mid-nineteenth century? Surely,

it could only be in a fiction? In his Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel The

Underground Railroad, African American writer Colston Whitehead (born 1969)

takes his readers in a reverse journey from a metaphor to the imagined reality

of an impossible railroad with the inviolable truth of bondage hanging as a

constant backdrop.

It is the story of

Cora, a third-generation slave born in a cotton farm in Georgia who was at the

cusp of womanhood. Cora, who didn’t “have” a father like many other slaves,

also had the misfortune as she had been abandoned by her feisty mother who ran

away. Deep within, Cora nursed a desire to trace her mother and confront her,

but she did not seriously consider the option of running away, which wasn’t much

of an option in any case.

Yet, one moonlit

night, she escapes because of a combination of circumstances and a newly

recruited slave, Caesar who had befriended her. Caesar was like no coloured man

Cora “had ever met,” because he could read and write, a fact which he concealed

for his life, as having even an elementary education was a crime for a slave and

it would attract severe punishment. Cora and Caesar don’t get into a physical relationship

but continued as comrades in a shared quest for freedom.

They outrun and

outwit their pursuers, manage to get the better of a vigilante group, and reach

a shelter offered by a stooped grey-haired white Pennsylvanian, Mr. Fletcher.

Fletcher, who abhors “slavery as an affront before God”, smuggles them out to

the nearest railroad station, taking enormous risk – like every other person

who collaborates with the railroad, irrespective of the colour of their skin.

After narrowly

winning the first round against the southern white man who “was spat from the

loin of the devil ….” Cora and Caesar climb down a steep staircase hidden

beneath a trapdoor to a platform of the Underground Railroad. Their real

journey begins.

Cora experiences “civilised”

white people in South Carolina who do not brutalize her body, but are equally keen

to own her mind, until the veneer of civilisation is flaked away one evening in

a sudden burst violence that separates her from Caesar.

In North Carolina,

after Cora sees miles of dead blacks hanging from trees, a kindly and extremely

scared white man and his wife hide her and her chamber pot, on an airless

platform in their attic, where Cora continues to nurse her dream of meeting

mother. From a hole in the wall of her hideout made by an earlier fugitive,

Cora watches a town square and a town without a black soul except when one is

ferreted out of a safe haven like Cora’s, and is savagely done to death along

with the white family that sheltered them, loudly cheered on by an ecstatic crowd.

Cora stays there for months, until her luck runs out, and her hosts’.

Cora is back in

shackles, this time, not metaphorically. She is chained to the floor of a wagon,

perhaps closing a circle that began with her grandmother’s journey across the

Atlantic.

As she heads

towards a terrible future, her journey, wildly oscillating between despair and

hope, traces the changing landscape and people of different southern states

while America moves towards an inevitable bloodbath and Civil War.

Colson Whitehead’s

novel, a story of enormous courage and resilience, resonates in our time as it

opens our eyes to the depths people can climb down when hatred captures the

mind of an entire community. Using a gruesome chapter of American and world

history as the backdrop, Whitehead retells – in captivating prose – the story

of tribalism and violence that are innate to humans.

The story makes us

think if our species has a future.

Colson Whitehead / The Underground Railroad / First Anchor Books

edition, 2018 / www.anchorbooks.com /

Copyright © 2016 by Colson Whitehead

Monday, 31 August

2020 / 1453 words