THE WAR WILL END

The war will end

The leaders will shake hands

The old woman will keep waiting for her

martyred son

The girl will wait for her beloved husband

And those children will wait for their hero

father

I don’t know who sold our homeland

But I saw who paid the price

*

THE ID CARD

Write down:

I am an Arab.

My ID card number is 50,000.

My children: eight

And the ninth is coming after the summer.

Are you angry?

Write down:

I am an Arab.

I work with my toiling comrades in a

quarry.

My children are eight,

And out of the rocks

I draw their bread,

Clothing and writing paper.

I do not beg for charity at your door

Nor do I grovel

At your doorstep tiles.

Does that anger you?

Write down:

I am an Arab,

A name without a title,

Patient in a country where everything

Lives on flared-up anger.

My roots…

Took firm hold before the birth of time,

Before the beginning of the ages,

Before the cypress and olives,

Before the growth of pastures.

My father… of the people of the plough,

Not of noble masters.

My grandfather, a peasant

Of no prominent lineage,

Taught me pride of self before reading of

books.

My house is a watchman’s hut

Of sticks and reed.

Does my status satisfy you?

I am a name without a title

Write down:

I am an Arab.

Hair coal-black,

Eyes brown,

My distinguishing feature:

On my head a koufiyah topped by the igal,

And my palms, rough as stone,

Scratch anyone who touches them.

My address:

An unarmed village—forgotten—

Whose streets are nameless,

And all its men are in the field and

quarry.

Are you angry?

Write down:

I am an Arab

Robbed of my ancestors’ vineyards

And of the land cultivated

By me and all my children.

Nothing is left for us and my grandchildren

Except these rocks…

Will your government take them too, as

reported?

Therefore,

Write at the top of page one:

I do not hate people,

I do not assault anyone,

But … if I get hungry,

I eat the flesh of my usurper.

Beware … beware … of my hunger,

And of my anger.

[At the age of 24, on 1 May 1965, when a young Darwish read his poem “Identity Card” to a crowd in a Nazareth cinema, there was a tumultuous response. Within days, the poem spread throughout the country and the Arab world.]

*

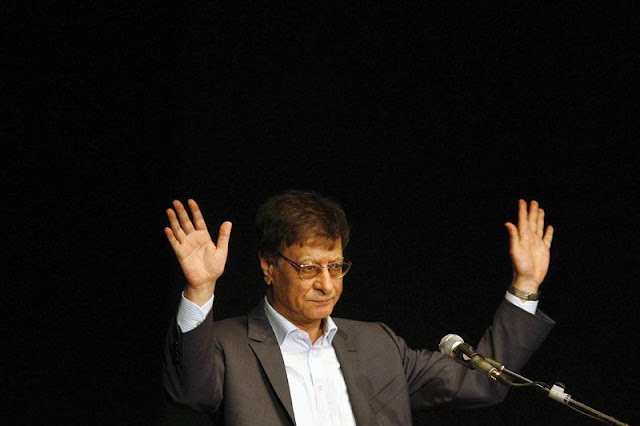

Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008) was the unofficial Palestinian National Poet in his lifetime. He wrote about the anguish of being uprooted and of exile.

Born in a family of land owners in 1941, he was taught to read by his grandfather as is mother was illiterate. When he was seven, Israeli forces attacked his village al-Birwa and razed it to the ground to prevent its inhabitants from returning. Darwish’s family fled to Lebanon. A year later, they returned to a different place in Israel. Darwish attended high school and eventually moved to Haifa, the third largest city in Israel.

He published his first book of poetry, WINGLESS BIRDS at the age of 19. He initially published his poems in the literary periodical of the Israeli Communist Party, eventually becoming its editor. Later, he was assistant editor of a literary periodical published by the Israeli Workers Party.

Darwish left Israel in 1970 to study in the Soviet Union for a year, before moving to Egypt and Lebanon. When he joined the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1973, he was banned from returning to Israel. But in 1995, Darwish was allowed to settle in Ramallah, a major Palestinian city on the West Bank, where he said it felt living in exile.

After the Six-Day-War of 1967, when Eastern Jerusalem and the West Bank were annexed by Israel, Darwish, “as a Palestinian poet of the Resistance committed himself to the ... objective of nurturing the vision of defeat and disaster, so much so that it would ‘gnaw at the hearts’ of the future generations.”

A central theme in Darwish's poetry is the concept of homeland. The poet Naomi Shihab Nye wrote Darwish “is the essential breath of the Palestinian people, the eloquent witness of exile and belonging ...”

Over his lifetime, Darwish published eight books of prose and over 30 volumes of poetry and, including the FEWER ROSES and OTHER BARBARIANS WILL COME. His work has been published in 20 languages.

Darwish said Arthur Rimbaud and Allen Ginsberg were his literary influences. He also admired the Hebrew poet Yehuda Amichai, but described his poetry as a “challenge to me, because we write about the same place. He wants to use the landscape and history for his own benefit, based on my destroyed identity. So we have a competition: who is the owner of the language of this land? Who loves it more? Who writes it better?”

Mahmoud Darwish died in 2008 at the age of 67, after a heart surgery in Houston, Texas.

His funeral was attended by the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, thousands of people, and several left-wing Israeli parliament members. After the ceremony, thousands of followers joined the cortege on the way to the Palestinian Palace of Culture, where Mahmoud Darwish was laid to rest.

On 5 October 2008, the International Literature Festival Berlin held a worldwide reading in memory of Mahmoud Darwish.

[The picture of Mahamoud Darwish and the poem THE ID CARD is from Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, November-December 2017 issue, which is available at https://www.wrmea.org/017-november-december/id-card-by-mahmoud-darwish-a-translation-and-commentary.html.

The poem THE WAR WILL END is from a twitter feed of Fakrh-e-Alam, a Pakistani pilot, singer, songwriter, and actor.

Information on Mahamoud Darwish is from the Wikipedia and other sources.]

23 January 2021